Overview

Diagnosis of Long QT Syndrome

To diagnose long QT syndrome (LQTS), a healthcare professional performs a physical exam, asks about symptoms, medical history, and family history, and listens to the heart with a stethoscope. If an irregular heartbeat is suspected, the following tests may be done to confirm the diagnosis.

Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

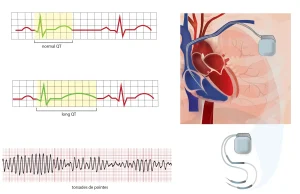

An ECG is the most common test used to diagnose long QT syndrome. It records the electrical signals in the heart through electrodes placed on the chest, arms, and legs.

- The QT interval measures the time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave.

- A prolonged QT interval indicates that the heart takes longer than normal to recharge between beats.

- In a serious complication called torsades de pointes, the waves appear twisted.

If symptoms are infrequent and not captured on a standard ECG, portable monitoring devices may be used:

Holter monitor

A small portable ECG device worn for a day or two to record heart activity during normal daily routines.

Event recorder

A device worn for about 30 days that records only during symptoms (activated manually or automatically when an irregular rhythm is detected).

Some smartwatches can also perform ECG recordings — discuss this option with your healthcare professional.

Exercise stress tests

These tests monitor the heart while walking on a treadmill or pedaling a stationary bike (or using medicine to mimic exercise). They show how the heart responds to physical activity. An echocardiogram may be performed at the same time.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing can confirm inherited long QT syndrome by identifying specific gene changes. Coverage should be checked with your insurer.

- Family members may also be offered testing.

- A genetic counselor should be consulted before and after testing, as not all inherited cases are detected by current tests.

Treatment Options for Long QT Syndrome

Treatment for long QT syndrome focuses on preventing irregular heartbeats and sudden cardiac death. Options are chosen based on symptoms and the specific type of LQTS, even if symptoms are rare.

Lifestyle changes

Certain activities, triggers, or competitive sports may need to be avoided (discussed individually with your healthcare team).

Medications

Beta blockers

These medicines slow the heart rate and reduce the risk of long QT episodes. Commonly used examples include nadolol (Corgard) and propranolol (Inderal LA, InnoPran XL).

Mexiletine

When taken with a beta blocker, this heart rhythm medicine can help shorten the QT interval and lower the risk of fainting, seizures, or sudden cardiac death.

If a medicine is causing acquired long QT syndrome, safely stopping it (under medical guidance) may resolve the condition. For some people with acquired LQTS, intravenous fluids or minerals such as magnesium may be given.

Surgery or other procedures

Left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) surgery

Surgeons remove specific nerves on the left side of the spine that affect heart rhythm. This reduces the risk of sudden cardiac death when beta blockers are ineffective or not tolerated.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD)

A device placed under the skin near the collarbone that continuously monitors heart rhythm and delivers shocks to restore normal rhythm if a dangerous arrhythmia occurs.

- Most people with LQTS do not need an ICD, but it may be considered for high-risk individuals or certain athletes.

- Placement requires surgery and carries risks such as inappropriate shocks; benefits and risks should be carefully discussed, especially in children.

Advertisement