Overview

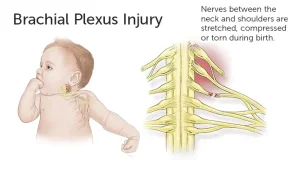

Brachial plexus injury occurs when the network of nerves that sends signals from the spinal cord to the shoulder, arm, and hand is stretched, compressed, or torn. These injuries can range from mild and temporary to severe and permanent. Brachial plexus injuries commonly result from trauma, childbirth complications, or sports-related accidents and can significantly affect arm movement and sensation.

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the severity and type of nerve damage and may involve one or both arms.

• Weakness or inability to move the shoulder, arm, or hand

• Loss of sensation or numbness in the arm or hand

• Burning, stinging, or electric shock–like pain

• Partial or complete paralysis of the affected arm

• Loss of reflexes in the shoulder or arm

• Muscle wasting with long-term nerve damage

Causes

Brachial plexus injuries occur when the nerves are damaged due to excessive force or pressure.

• Trauma from motor vehicle accidents or falls

• Sports injuries, especially contact sports

• Stretching of the neck and shoulder during difficult childbirth

• Tumors or inflammation affecting the nerve network

• Penetrating injuries such as knife or gunshot wounds

• Surgical complications involving the neck or shoulder

Risk factors

Certain factors increase the likelihood of sustaining a brachial plexus injury.

• Participation in contact or high-impact sports

• High-speed vehicle accidents

• Large birth weight or prolonged labor during delivery

• Shoulder or neck surgeries

• Tumors near the neck or upper chest

Complications

Complications vary depending on injury severity and timeliness of treatment.

• Chronic pain or neuropathic pain

• Permanent weakness or paralysis of the arm

• Loss of fine motor skills and hand function

• Muscle stiffness or joint contractures

• Reduced quality of life and functional independence

Prevention

Not all brachial plexus injuries can be prevented, but risk can be reduced.

• Use protective gear during contact sports

• Practice safe driving and wear seat belts

• Ensure proper obstetric care during labor and delivery

• Seek early medical evaluation after neck or shoulder trauma

• Follow safety guidelines during surgical procedures

Advertisement