Overview

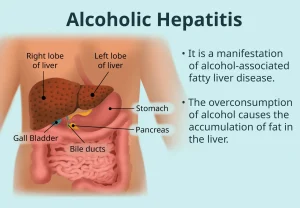

Alcoholic hepatitis is a form of liver damage marked by swelling and inflammation caused by alcohol use. This inflammation harms liver cells and interferes with normal liver function. The condition most often develops in people who have consumed large amounts of alcohol over many years, though it can also occur in people who binge drink.

Healthcare experts increasingly use the term alcohol-associated hepatitis to reduce stigma and emphasize that this is a medical condition rather than a moral failing. Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious type of alcohol-associated liver disease. This group of conditions ranges from fatty liver caused by alcohol to severe and permanent scarring of the liver, known as cirrhosis.

Not everyone who drinks heavily develops liver disease, but the risk is significant. Research suggests that up to one in three people with alcohol use disorder will develop some form of alcohol-related liver disease. Stopping alcohol use is the most important part of treatment. Continuing to drink after a diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis greatly increases the risk of liver failure and death. Proper nutrition also plays a key role in recovery.

Symptoms

The most common symptom of alcoholic hepatitis is yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes, called jaundice. Jaundice occurs when bilirubin, a yellow waste product formed from the breakdown of red blood cells, builds up in the blood because the damaged liver cannot remove it effectively. Yellowing of the skin may be harder to notice depending on skin tone.

Other symptoms may include:

-

Loss of appetite

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Tenderness or discomfort in the abdomen

-

Low-grade fever

-

Tiredness and weakness

-

Pain in the upper right side of the abdomen, where the liver is located

Many people with alcoholic hepatitis are malnourished. Heavy alcohol use can suppress appetite, and alcohol often replaces food as the main source of calories. Alcohol also interferes with how the body absorbs and uses nutrients.

In advanced cases, additional symptoms may appear:

-

Fluid buildup in the abdomen, called ascites

-

Confusion or unusual behavior due to toxin buildup, known as hepatic encephalopathy

-

Bleeding in the digestive tract from enlarged veins in the esophagus or stomach, called varices

-

Kidney and liver failure

Causes

Alcoholic hepatitis develops when the liver processes alcohol and produces toxic byproducts that damage liver cells. These toxins trigger inflammation and stress within the liver. The immune system responds to the damage, but this response can worsen inflammation and further injure liver tissue.

Alcohol also weakens the lining of the intestines, allowing bacteria and their toxins to enter the bloodstream and reach the liver. This process increases liver inflammation and injury.

Over time, fat can accumulate in the liver. When fat buildup, inflammation and liver cell damage occur together in someone with metabolic dysfunction and significant alcohol use, the condition may be referred to as metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-associated liver disease. This term reflects the overlap between metabolic liver disease and alcohol-related injury.

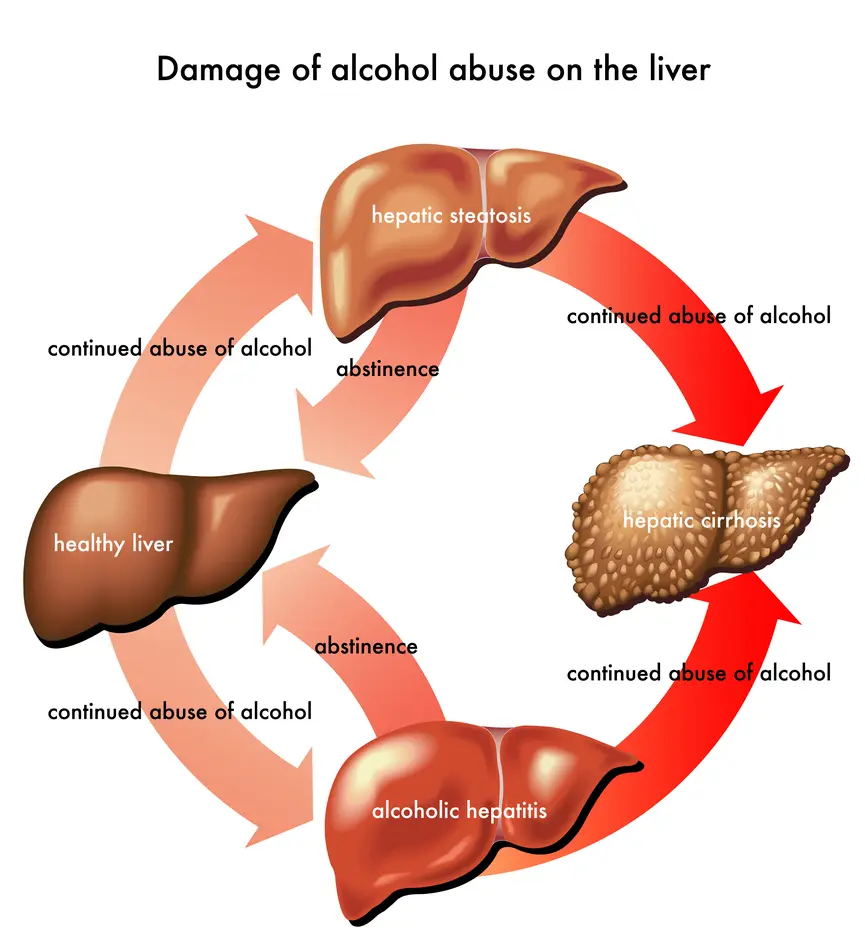

When inflammation becomes severe enough to cause jaundice or sudden liver failure, the condition is diagnosed as alcoholic hepatitis. As the disease progresses, liver cells die, bile builds up and healthy tissue is replaced by scar tissue. Early scarring is called fibrosis. With ongoing damage, fibrosis can progress to cirrhosis, which is usually permanent.

Many people are diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis only after fibrosis or cirrhosis has already developed. Fibrosis may improve with complete alcohol abstinence, but cirrhosis typically cannot be reversed. Some people have alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis at the same time.

Other substances, such as certain medications, herbal supplements or toxins, can also inflame the liver. This is known as toxic hepatitis. Although alcoholic hepatitis is sometimes grouped under this term, it is considered a distinct condition caused specifically by alcohol.

Certain factors can worsen alcoholic hepatitis, including:

-

Other liver diseases, such as hepatitis C

-

Poor nutrition or vitamin deficiencies

Risk factors

The greatest risk factor for alcoholic hepatitis is the amount of alcohol consumed and the length of time a person drinks. One standard drink contains about 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is roughly equal to a 12-ounce beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine or a 1.5-ounce shot of liquor.

For women, drinking three to four drinks per day for six months or longer increases the risk. For men, four to five drinks per day for six months or longer raises the risk. Not everyone who drinks this much develops alcoholic hepatitis, but the likelihood increases significantly.

Additional risk factors include:

-

Sex, with women generally at higher risk due to differences in alcohol metabolism

-

Being overweight or obese

-

Genetic factors that influence how the body processes alcohol

-

Race and ethnicity, with higher risk reported in some Black and Hispanic populations

-

Binge drinking

-

Use of acetaminophen while drinking alcohol

-

Prior bariatric surgery, which alters alcohol absorption and raises blood alcohol levels

-

Coexisting viral hepatitis, especially hepatitis C

Alcoholic hepatitis is not contagious. Unlike viral hepatitis, it cannot be spread from person to person.

Complications

Complications of alcoholic hepatitis often result from liver scarring and cirrhosis, which disrupt blood flow through the liver and increase pressure in the portal vein. This pressure buildup can lead to serious health problems.

Possible complications include:

-

Enlarged veins in the esophagus or stomach, called varices, which can rupture and cause life-threatening bleeding

-

Fluid buildup in the abdomen, known as ascites, which may become infected

-

Mental status changes due to toxin buildup in the brain, called hepatic encephalopathy

-

Kidney failure caused by reduced blood flow to the kidneys, known as hepatorenal syndrome

-

Cirrhosis, which can lead to liver failure and increases the risk of liver cancer

-

Death, especially in severe cases or when alcohol use continues

The outlook depends on disease severity and whether alcohol use stops. Mild to moderate cases have a relatively high short-term survival rate. Severe alcoholic hepatitis carries a much higher risk of death, particularly if complications such as infection or kidney failure occur.

Having both hepatitis C and alcoholic hepatitis places extreme stress on the liver and increases the risk of liver failure, cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Prevention

The most effective way to prevent alcoholic hepatitis is to avoid alcohol altogether. If alcohol is consumed, it should be in moderation. For healthy adults, moderation generally means up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men. Lower limits may apply after weight-loss surgery.

Other prevention steps include:

-

Getting screened and treated for hepatitis C

-

Avoiding alcohol when taking medications that can damage the liver

-

Reading medication labels carefully, especially for acetaminophen

-

Talking with a healthcare professional before mixing alcohol with prescription or over-the-counter medicines

For people with existing liver disease, even small amounts of alcohol can worsen liver damage. Early medical care, healthy nutrition and complete alcohol abstinence are key to reducing the risk of serious complications.

Advertisement