Overview

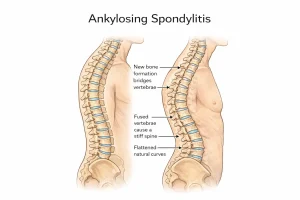

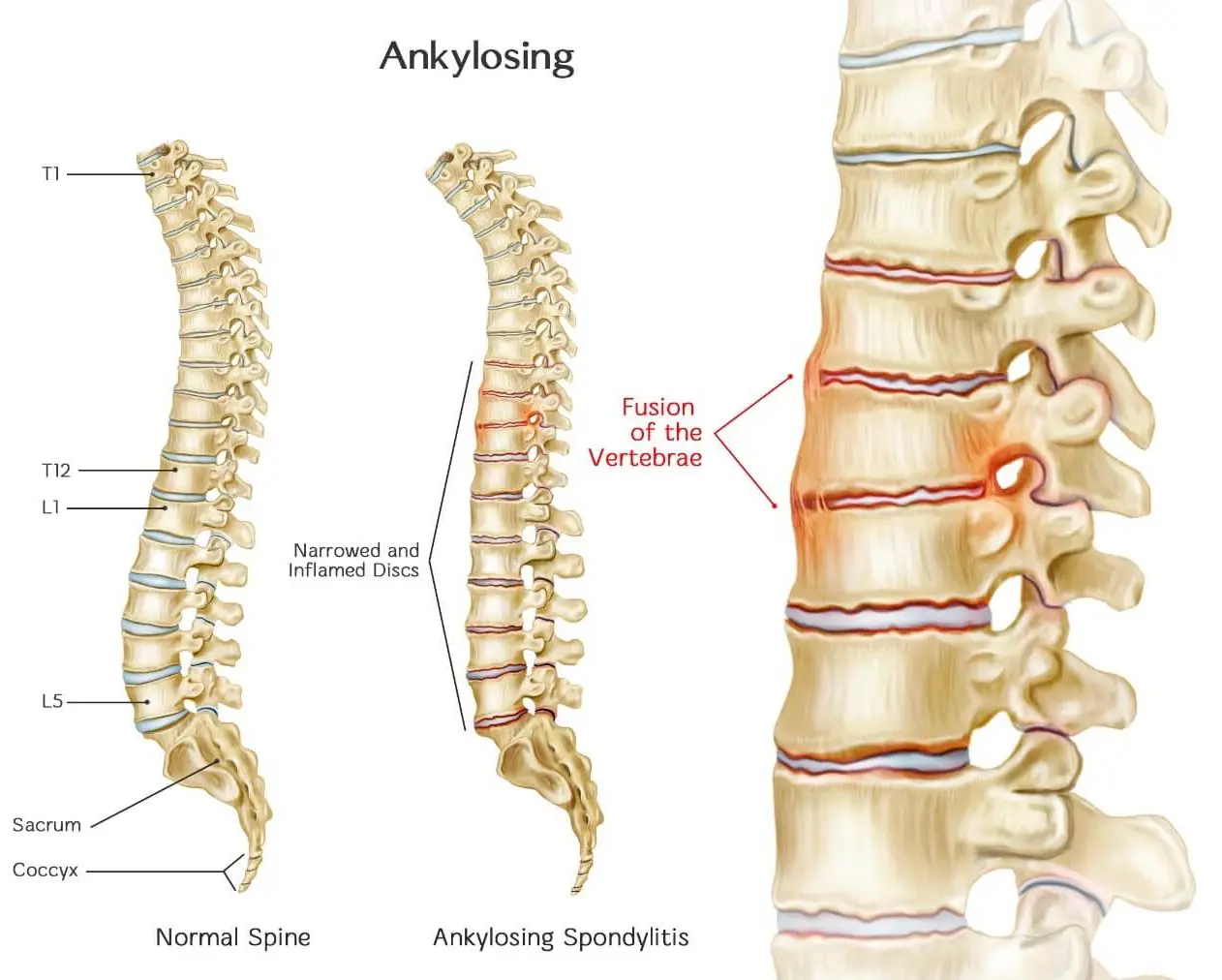

Ankylosing spondylitis, also known as axial spondyloarthritis, is a long-term inflammatory condition that primarily affects the spine. Persistent inflammation can cause the vertebrae to gradually fuse together. This fusion reduces flexibility in the spine and may result in a forward-stooped or hunched posture. When the joints connecting the ribs to the spine are involved, chest expansion can be limited, making deep breathing more difficult.

Axial spondyloarthritis includes two forms. When inflammation-related changes are visible on X-rays, the condition is referred to as ankylosing spondylitis. When X-rays do not show changes but symptoms, blood tests, and imaging such as MRI confirm inflammation, it is called nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

Symptoms often begin in late adolescence or early adulthood. In addition to spinal involvement, ankylosing spondylitis can cause inflammation in other parts of the body, most commonly the eyes, leading to a condition called uveitis. While there is no cure, treatment options can reduce pain, improve mobility, and help slow disease progression.

Symptoms

Early signs of ankylosing spondylitis commonly include persistent back pain and stiffness, especially in the lower back and hips. These symptoms are often worse in the morning or after long periods of rest and may improve with movement or exercise. Neck pain and ongoing fatigue are also common.

Other symptoms may develop depending on which areas are affected. Pain and stiffness can come and go, with some people experiencing flare-ups followed by periods of improvement. Inflammation may also affect areas beyond the spine, leading to eye discomfort, skin changes, or digestive symptoms.

The areas most often involved include:

-

The sacroiliac joints between the base of the spine and the pelvis

-

The vertebrae of the lower back

-

Sites where tendons and ligaments attach to bones, especially along the spine or the back of the heel

-

The cartilage connecting the ribs to the breastbone

-

The hip and shoulder joints

Causes

The exact cause of ankylosing spondylitis is not fully understood. Genetic factors play a significant role in increasing susceptibility to the disease. Many people with ankylosing spondylitis carry a gene known as HLA-B27, which is associated with a higher risk of developing the condition.

However, not everyone with the HLA-B27 gene develops ankylosing spondylitis, and some people with the condition do not carry this gene. This suggests that other genetic and environmental factors also contribute to disease development.

Risk factors

Several factors may increase the likelihood of developing ankylosing spondylitis:

-

Younger age, as symptoms typically begin in late adolescence or early adulthood

-

Genetic predisposition, particularly the presence of the HLA-B27 gene

Having one or more risk factors does not guarantee that the condition will develop, but it may increase overall susceptibility.

Complications

In more advanced cases, long-standing inflammation triggers the formation of new bone as the body attempts to repair damaged tissue. Over time, this new bone can bridge the spaces between vertebrae, causing sections of the spine to fuse. This fusion leads to stiffness, reduced mobility, and worsening posture.

If the joints of the chest wall become stiff, lung expansion may be limited, making deep breathing more difficult. Additional complications may affect other organs and systems.

Possible complications include:

-

Eye inflammation known as uveitis, which can cause sudden eye pain, redness, light sensitivity, and blurred vision

-

Compression fractures of the spine due to weakened bones, potentially affecting spinal nerves

-

Heart-related issues, including inflammation of the aorta, which can alter the function of the aortic valve and increase the risk of heart disease

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent ankylosing spondylitis, especially in individuals with a genetic predisposition. However, early diagnosis and consistent treatment can help manage symptoms, preserve spinal flexibility, and reduce the risk of long-term complications. Maintaining regular physical activity, following prescribed treatments, and monitoring symptoms closely may improve long-term outcomes and quality of life.

Advertisement