Overview

Calciphylaxis is a rare but serious condition characterized by calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels in the skin and fatty tissues. This leads to reduced blood flow, skin ischemia, and painful skin lesions that can progress to ulcers and tissue necrosis. Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in people with advanced kidney disease, particularly those on long-term dialysis, but it can also develop in individuals without kidney failure. The condition carries a high risk of infection and mortality if not managed promptly.

Symptoms

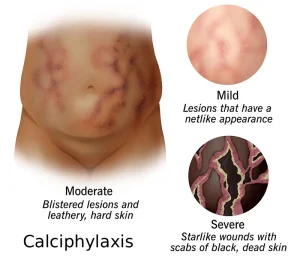

Symptoms of calciphylaxis often begin with skin changes and progressively worsen as blood flow becomes increasingly restricted.

Common symptoms include:

-

Painful skin patches or nodules

-

Livedo reticularis or mottled skin appearance

-

Firm, tender areas beneath the skin

-

Dark or purplish skin discoloration

As the condition progresses, symptoms may include:

-

Non-healing skin ulcers

-

Blackened areas of dead tissue

-

Severe, persistent pain

-

Signs of skin infection such as redness, warmth, or drainage

Causes

Calciphylaxis develops due to abnormal calcium and phosphate metabolism, leading to calcium deposition in blood vessel walls. This process causes narrowing and blockage of blood vessels, resulting in tissue damage.

Contributing causes include:

-

Imbalance of calcium and phosphate levels

-

Vascular calcification

-

Impaired blood flow to the skin and subcutaneous tissue

The exact mechanism is not fully understood, but multiple metabolic and inflammatory factors are believed to play a role.

Risk Factors

Several medical and lifestyle factors increase the risk of developing calciphylaxis, particularly in individuals with chronic illness.

Key risk factors include:

-

End-stage kidney disease and dialysis

-

Elevated calcium-phosphate product

-

Hyperparathyroidism

-

Diabetes mellitus

-

Obesity

-

Use of warfarin

-

Female sex

-

Low blood albumin levels

Calciphylaxis can also occur in patients without kidney disease, though this is less common.

Complications

Calciphylaxis can lead to severe complications due to skin breakdown and systemic infection.

Potential complications include:

-

Chronic, non-healing wounds

-

Severe skin and soft tissue infections

-

Sepsis

-

Poor wound healing

-

High risk of mortality

Pain and recurrent infections significantly impact quality of life and overall prognosis.

Prevention

There is no guaranteed way to prevent calciphylaxis, but risk can be reduced by managing underlying conditions and metabolic imbalances.

Preventive measures may include:

-

Careful monitoring and control of calcium and phosphate levels

-

Appropriate management of kidney disease

-

Reviewing medications that may increase risk under medical supervision

-

Maintaining proper nutrition and protein levels

-

Early evaluation of suspicious skin changes

Early diagnosis and coordinated medical care are critical to improving outcomes and reducing complications associated with calciphylaxis.

Advertisement